He was among the few CPM leaders who didn’t ideologically over-analyse whether the party should ally with Congress, earlier identified as communists’ chief adversary, to take on BJP when the latter became a governing party under Vajpayee’s leadership.

During the 2024 campaign, he insisted Modi-led BJP should be taken on in state-by-state contests, via alliances. An analysis partly borne out by results. Interestingly, CPM’s ideological purists still don’t formally acknowledge the party’s alliance with Congress, never mind that CPM is a part of INDIA bloc.

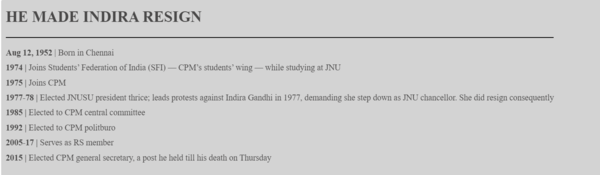

That Yechury, as a student politician, had forced Indira Gandhi to step down as JNU chancellor made his later pragmatism all the more noticeable. That he stayed away from Naxalites in 1970s, because that offshoot of Marxist politics declared loyalty to China’s communists, was another indication of his practical political sense. As he said in 2014, when Modi took office for the first time: “Conditions have changed, so our analysis and alignment accordingly will change”.

If some assessments of his pragmatism compare him to the other practical communist, Harkishen Singh Surjeet, an astute alliance builder, it should be noted that the difference in the success rate of the two is explained largely by CPM having been in a politically more commanding position during Surjeet’s heydays.

Yechury’s easygoing nature wasn’t a later day political makeover. Even as a student activist he wasn’t known for being overbearing or loudly declaratory. Engaging in debates was his style, and witty one-liners were his rhetorical signature. Many politicians, including communists, are given to ranting. Yechury never was. The other standout feature was unlike many fellow Marxists, he avoided jargon. Again, unlike doctrinaire Marxists, he was always interested in not just class but also social groups and religion. He understood the latter were valuable in understanding Indian society.

Telugu was his mother tongue. In the party forum and in meetings, he preferred English because he felt that political formulation came more easily to him in that language. But he gave public speeches in Hindi. During his two-term stint in the Rajya Sabha from Bengal, he tried to speak in Bengali during his conversations with Bengali journalists.

Born to a Telugu Brahmin family, Yechury had refused to wear the sacred thread and chant slokas. He said he was the first communist in his family. But he didn’t discount philosophical debates embedded in the ancient religious texts. An open-mindedness that later helped him debate the Hindu Right.

Those who knew him well said one of Yechury’s defining qualities as a politician was that he was more interested in finding commonalities than divergences between parties and groups. These attributes served him well in Parliament, where his articulation stood out as the general quality of parliamentary interventions worsened. When he ended his Rajya Sabha term in 2017, Samajwadi Party MP Ram Gopal Yadav’s tribute stood out. But he wasn’t the only MP who felt the House would miss Yechury.

Of course, as the Left’s electoral footprint shrank, so did the national political importance of CPM leaders, including Yechury. The high point was between 2004 and 2008 — from the time UPA-1 was formed till when CPM withdrew support to Manmohan Singh’s govt over the Indo-US nuclear deal.

It’s rare for Indian politicians, including communists, to introspect publicly. But Yechury proved an exception when, after UPA-2 took office, he admitted that his party hadn’t been able to explain its stand on the nuclear deal to voters, who gave a Congressled coalition a healthy victory. He was perhaps the only politburo member to do so.

Losing Bengal to TMC dealt a blow to CPM and its leaders they haven’t recovered from. Yechury, along with other CPM leaders, rarely made national headlines.

But his international communist connections did make him very relevant when in 2009, UPA govt took his help to contact Nepal’s Maoist leader Prachanda, who later became PM.

Yechury’s last public message came the day he was shifted from the ICU to a general bed at AIIMS, Delhi. The recorded message was his tribute to another communist stalwart, former chief minister of Bengal, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, who passed away recently.

Yechury was dealing with a deeply personal tragedy when he fell ill. He lost his son Ashish to Covid in 2021. He was never quite the same after that, those close to him said. The father in him was bereft. But it speaks to his abilities as a politician that the pragmatic communist in him soldiered on.