The recent case where a Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) bus driver passed away after cardiac arrest while on duty, has set off discussions on rising poor health outcomes in our cities.

Our cities are spread over pockets and layers. These pockets house the most marginalised and vulnerable urban citizens such as informal workers and migrant workers. Our cities run, literally and figuratively, because of bike-borne gig workers, cab and auto drivers, bus drivers and conductors. Our cities shine and are clean because of sanitation workers who are awake before the city does to clean the roads, clear the garbage bins and transport the garbage to sorting stations, waste lands, or landfills, all while staying deprived of hygiene and nutrition while at work. Most of them are not on contract and without health insurance.

Poor implementation of policies

As we discuss this, India has a national non-communicable diseases (NCD) surveillance policy, with screening for NCD risks at the community level, aimed at preventive and promotive pathways for NCD care and treatment pathways. Though these policies are often subscribed from global bodies, they are poorly implemented. Health systems in urban areas are overburdened, fragmented and broken, which is a function of poor urban design and rapid urbanisation.

With over half of the world’s population living in urban areas, this figure is projected to reach 70% by 2050. India’s workforce is characterised by significant inter-State migration, with approximately 41 million people moving between States (Census 2011). This dynamic process, constituting nearly 29% of the total migration rate (Periodic Labour Force Survey 2020-21), highlights the fluidity of labour markets. Notably, a substantial portion of the urban population, estimated at 49% (UN-Habitat/World Bank, 2022), lives in slums, further underscoring the complex socio-economic landscape of India’s cities.

The health burden in urban India

Poor urban communities face a triple health burden: hazardous work environments, limited health-care access, and financial vulnerability during health crises, that are exacerbated by social and economic marginalisation. As for national data on health indicators, NFHS data showed a decline in tobacco and alcohol consumption from 2005-06 to 2019-21 (NFHS 3 and 5), which is alarmingly juxtaposed with a rise in hypertension, diabetes, and obesity rates (NFHS 4 and 5).

Symptomatically, NCDs are silent, necessitating regular screening which needs to sit within a robust health promotion and referral system. The lack of understanding of the need for screening, early detection and preventive pathways for NCDs create catastrophic out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure, in turn jeopardising financial stability and impacting the overall livelihood and life trajectory of the entire family.

This writer’s experience of working with marginalised communities aligns with the fundamentals of social determinants of health (SDoH) which tie workplace, work, housing, community, family connections to health outcomes. Health in marginalised communities stems from social identities, work and employment, language, migration status, and accessing primary health systems.

In a country whose foundation of health systems sits on strong primary health care, it is problematic that the availability and access to publicly-run primary health care are abysmally poor among urban marginals. Public health systems are, by design, supposed to cater to all, and, most specifically, to the lowest 40% of the population. The idea of universal health coverage fails. Preventing OOP expenditure fails. And our urban marginals are laden with poor health outcomes, which, for many, runs across generations. This necessitates having an active dialogue between employers, municipalities, traffic systems, schools, as well as health systems. As interconnected systems, there is a need to co-create solutions with the community, and for the community.

Tapping technology

The framework

In this age of digital technology and ease of tech-based monitoring, we could bring real-time monitoring of parameters on the lines of ‘health in our hands’ for those who have hypertension and diabetes. Screening, as a methodology, has a two-fold advantage. It gives us evidence from the population level which could be used for epidemiological modelling and public health planning.

On the other hand, this creates awareness at the individual- and community-level for health risks. It makes room for the implementation of community based, co-created health promotion, and health education activities which are sustainable and in turn un-burden health systems. This also creates an awareness for pathways for health care, referral and knowledge on social protection schemes to limit OOP expenditure.

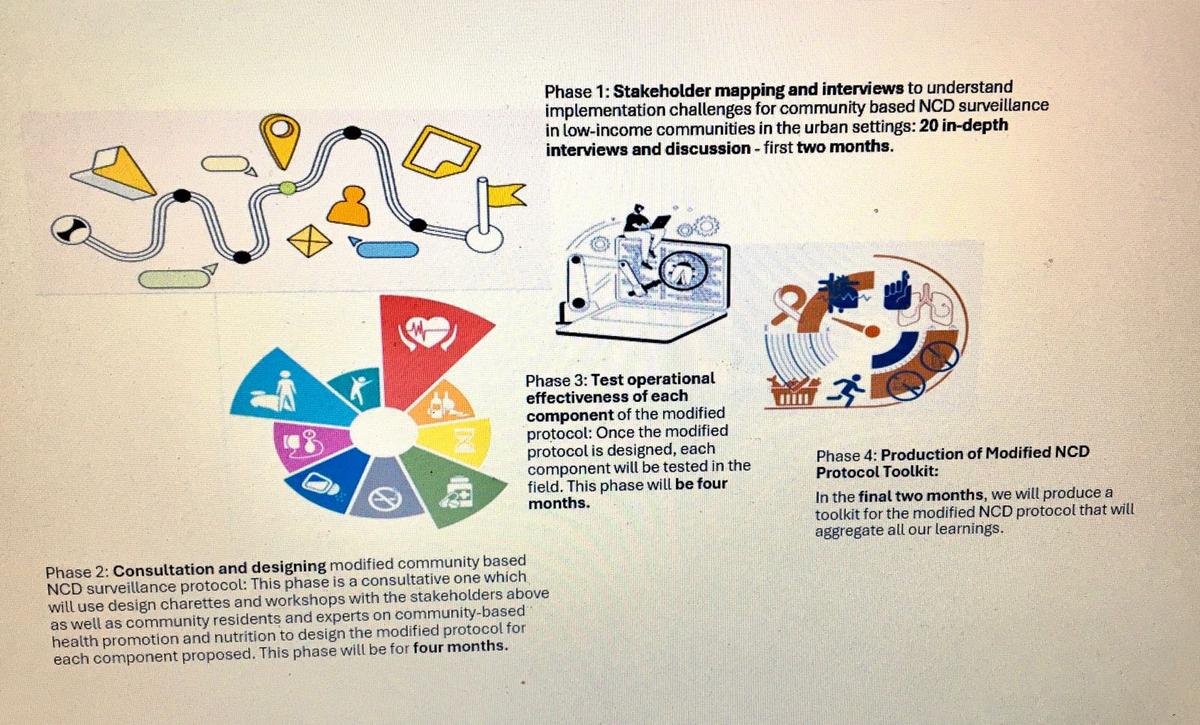

This is the time for State-level action plans for NCD health care, which lay an emphasis on access to primary health care for marginalised communities and poor urban neighbourhoods — migrants, informal workforce, people living in informal settlements. We need to join hands with urban local bodies, the city administration, health departments and community-based organisations, experts and think tanks and discuss ideas to create healthy cities for all. This should also lead to a scaling up of ideas for community-led, community-based NCD surveillance systems for marginalised urban settlements.

Aruna Bhattacharya leads the urban health domain at the School of Human Development, Indian Institute for Human Settlements. She is also the current Fellow of WomenLift Health’s SouthEast Asia 2024 cohort

Published – December 02, 2024 12:59 am IST